The Magnetic Epitaph

What a gravestone reveals about the dissemination of technology

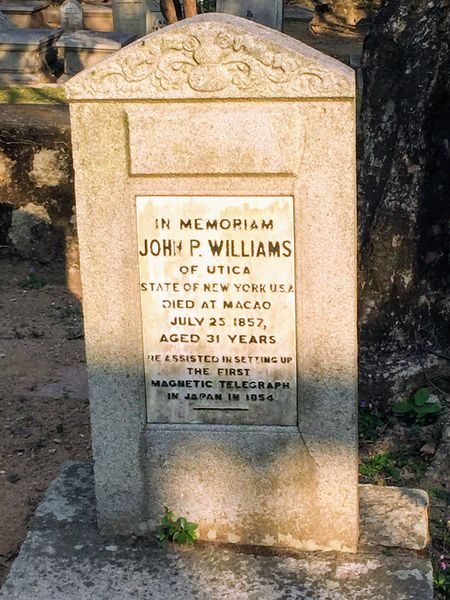

One warm January evening last year, I found myself alone in Macau’s Old Protestant Cemetery. I wandered around reading the inscriptions on the tombstones, communing with the spirits of 19th century traders, mariners, missionaries, diplomats... and telecoms engineers?

I had paused at the resting place of one John P. Williams, of Utica, New York State, who: “Died at Macao, 25 July 1857, aged 31 years. He assisted in setting up the first magnetic telegraph in Japan in 1854.”

I flashed back to a moment in my own life, arriving in Japan in 1996 to help install a new international telephone switch. It felt wholly modern then to be traversing the globe, plugging a few more connections into what has been called “the world’s largest machine” - the telephone network. Modern in some ways, perhaps, but any trails that were to be blazed had been blazed at least 142 years before I got there, according to this tombstone.

Curious, I looked further into the short life of John Williams and his telegraphic tale.

When the 1850s began, Japan was a feudal society, ruled by warlords and samurai. It had been closed to foreigners for two centuries, aside from highly restricted trade with the Chinese and Dutch.

The United States, reaching the limits of expansion within its own continent, saw Japan as an opportunity to grow its global footprint, and to outmanoeuvre the old European colonial powers.

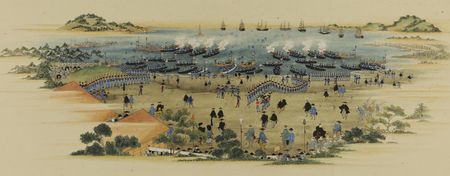

Accordingly, the US dispatched an armed fleet under Commodore Matthew Perry to make the Japanese an offer they couldn’t refuse: open their ports to trade or find out how far behind they lagged in military technology after 200 years of isolation.

The Japanese did the calculation and acceded to all of the United States’ demands.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Initial unpleasantness out of the way, friendly relations could commence.

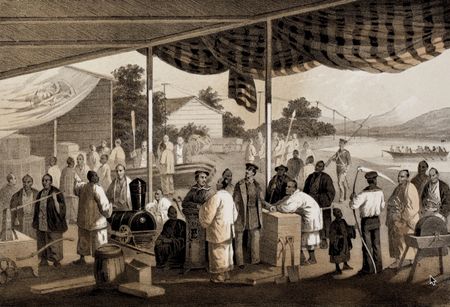

Perry had brought along samples of American manufactures to impress the locals, among them two telegraph terminals supplied by Samuel Morse, some miles of cable to connect them and batteries. Chief engineer William Draper and his assistant, John Williams, were seconded to Perry’s crew to accompany the equipment.

Co-opting local help, they erected a telegraph line a mile long at the treaty-signing ground at Yokohama. They then demonstrated the transmission of English, Dutch and Japanese over and over again for two weeks to an insatiably curious stream of Japanese visitors.

When Perry left for America, the telegraph was left behind as a gift.

Williams remained in the region, settling in China and becoming captain of a river steamer, the Spark, part of a small fleet that ran between Macau, Hong Kong and Canton. Occupational hazards included pirates and the occasional murderous mutiny by crew.

It was a turbulent time in China, then embroiled in a civil war known as the Taiping Rebellion. One of the bloodiest conflicts in history, it claimed between 20 million and 70 million lives. A localised faction, the Red Turbans, harried the towns of southern China and came close to taking the city of Canton itself in the summer of 1854.

As if China’s rulers didn’t have enough to contend with, the British were also agitating for trading privileges beyond those awarded in the treaty that ended the First Opium War in 1842. The result was the Second Opium War that commenced in 1856 with the British bombarding Canton from their ships.

The Chinese Imperial Commissioner in turn offered a bounty for British heads. The Americans and French were dragged into the conflict and, by December, 1856, the section of Canton hosting the foreign warehouses, banks, consulates and dwellings had been burned to the ground. John Williams and the Spark participated in the evacuation of foreign residents to the safety of Macau.

On the 15th of January, 1857, several hundred European residents of the nearby British colony of Hong Kong were poisoned by arsenic-laced bread from a Chinese-owned bakery. Neither the motive behind the poisoning nor the identity of the poisoner was ever established. Luckily, the amount of arsenic used was so much that it induced vomiting before it could kill its victims, much reducing the harm.

Although the poisoning caused no immediate fatalities, three deaths that occurred during the following months were ascribed to the lingering effects of the arsenic. One of those was that of John Williams, in July 1857, aged just 31.

In his short life, John Williams had a front row seat to many events of lasting significance. Perry’s mission to Japan triggered political revolution and the industrialisation, urbanisation and militarisation of that nation. Japan quickly progressed from a country seeking the ability to defend itself against Western powers to emulating the colonising activities of those same powers. Ultimately, it led to Japan’s declaration of war on the United States during WWII.

Likewise, China’s defeats during the First and Second Opium Wars and the humiliating treaties imposed thereafter still colour China’s relations with the West today.

Williams died long before any of this played out, of course, but he must have had a strong notion of his country’s rising power, and of his own part in America’s wielding of that power.

But his tombstone claims no stake in the belligerance of the time. I wonder if Williams was the author of his own epitaph, given the lengthy delay before the arsenic finally took him. If not, the task must certainly have fallen to his brother, Samuel Wells Williams, long term resident of China and official interpreter on Perry’s mission. Samuel would have known that John’s proudest moment was bringing a new technology to a new land.

I think Williams suspected from the reaction to his demonstrations that the telegraph and other technologies they had brought to Japan had touched a chord, that a fuse had been lit that would not be quenched.

If so, he was absolutely correct. The Japan that Williams encountered was pre-industrial but technologically very receptive.

Once the Americans left, the Japanese set about minutely examining the technology left behind, assigning teams to learn as much as possible, acquiring more equipment, translating texts, and sending students abroad to gain knowledge of the underlying magnetic and electrical principles.

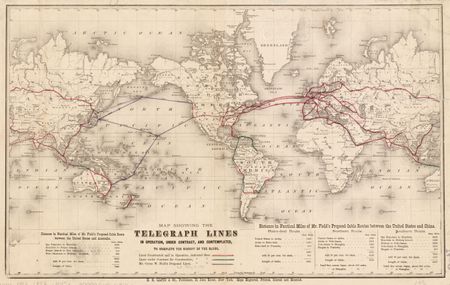

Within a few years they had more trial lines in operation. The first commercial telegraph in Japan began in 1869. By 1872, Japan was connected to Europe via the Trans-Siberian telegraph line.

This pattern of adopting, deconstructing and improving on technological innovation from elsewhere is one that Japan was still renowned for in the 20th century. Sony did it with the transistor, Toyota with lean production.

It must have delighted Williams to be able to share one of the wonders of the age with a fresh and eager audience. Reading between the lines of his epitaph, I reckon he knew that the impact of his time in Japan would be deep and positive, and would last far longer than the ignoble squabbles that preoccupy nations.

Sources

- An East India Company Cemetery: Protestant Burials in Macao, Volume 1, by Lindsay Ride, May Ride & Bernard Mellor. Hong Kong University Press, 1996.

- Forgotten Souls, A Social History of the Hong Kong Cemetary, by Patricia Lim. Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

- The Heaven and Earth Society and the Red Turban Rebellion in Late Qing China, by Jaeyoon Kim. Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, Volume 3, Issue 1, 2009.

- Samuel F.B. Morse, His Letters and Journals, Volume 2, by Samuel Morse. Cambridge University Press, 1914.

- Displaying the American Genius: The Electromagnetic Telegraph in the Wider World, by Yakup Bektas, The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 34, No. 2 (June 2001), pp. 199-232

- A journal of the Perry Expedition to Japan (1853-1854), by Samuel Wells Williams, Kelly & Walsh, 1910

- Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, by Matthew Calbraith Perry, United States Navy, 1856

- “Caution! The bread is poisoned”: The Hong Kong mass poisoning of January 1857, by Kate Lowe and Eugene McLaughlin, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 43:2, 2015, pp. 189-209

Previous: The Fashionable Chinese Puzzle

Next: Variations on a Logo